- Home

- John Plotz

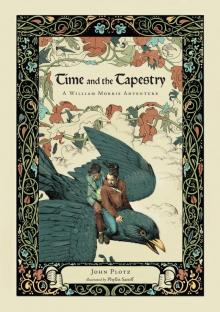

Time and the Tapestry

Time and the Tapestry Read online

Time and the Tapestry

Time and the Tapestry

A William Morris Adventure

JOHN PLOTZ

www.bunkerhillpublishing.com

Bunker Hill Publishing Inc.

285 River Road, Piermont

New Hampshire 03779, USA

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright text © 2014 John Plotz

Copyright illustrations © 2014 Phyllis Saroff

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013949578

ISBN 978–1–59373–145–8

Designed by JDL

Printed in China

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher of this book.

The Author’s royalties for this book will benefit the

William Morris Society in the United States

www.morrissociety.org

For further information on William Morris and the publisher

go to www.bunkerhillpublishing.com

For Helen Abrams (1912–2013)

Granny

CHAPTER ONE

Nobody But Us

This story begins the Friday Granny got the letter. “We regret to inform you”—she read it out to us matter-of-factly as we flopped down on our dusty old sofa—“that the age and origin of your Tapestry remain mysterious …”

I felt my ears go numb and I lost the rest. Ed sucked in his breath, like he’d been punched. I put my head down. I didn’t want to see what Granny’s face looked like, and I really didn’t want her to see mine.

So we’re losing the house, I told myself, losing it, losing it, losing it. No amount of repetition could make it sink in. It was the kind of thing that happens in old-fashioned books where kids wear flour-sack dresses and bake biscuits on a cookstove.

I started running through if only’s in my mind, like a filmstrip that wouldn’t stop. Each picture was something that could have made it all turn out differently. If only developers didn’t want to build a mall right where our house stands. If only the museum had decided to buy up everything in our house, or if only Granny had sold her Arts and Crafts antiques to that rich collector with the Lexus. Like a skipping CD, the biggest one of all kept looping back into my thoughts: If only our parents had never gotten on that flight …

Part of my brain likes to look down at life from an attic window. That part was wondering why I was letting myself get so upset over a letter. After all, Granny and Ed and I were pretty used to angry letters from the bank, or from developers who couldn’t wait to get their hands on what they liked to refer to as our “developable lot.”

Before the day this letter came, the Museum of Fine Arts had only meant Mr. Nazhar the curator coming over for tea and a look at some of Granny’s “trrreasures.” We loved the way he rolled his r’s, and the soft battered briefcase that he let Ed hold on his lap during the visit. And we couldn’t keep our eyes off his old-fashioned leather checkbook, which always came out toward the end.

At first he only took away beautifully printed books: “Kelmscott,” Granny said reverently, even though the author’s name on the crackly yellow covers might be John Keats, or John Milton, or Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Later it was ordinary things from our living room or even our kitchen—tiles, lamps, tables, glasses (“Webb glasses,” said Granny once in her quietest voice, stroking them softly). Hard to believe someone would visit a museum just to see things I’d held in my hands a hundred times.

In the six years after we came to live with Granny, Mr. Nazhar came to visit a lot. He wasn’t the only visitor, though. Sometimes we’d hear a roar and look out the front windows to see a bald, sweating man climbing slowly out of his shiny, sleek car: “Lexus: The Relentless Pursuit of Perfection!” Ed whispered to me once in a soft, solemn voice. Lexus guy smiled a lot, but I noticed that he always seemed to be looking right through us, as if we were a wispy curtain, barely visible, standing between him and his future Arts and Crafts collection. We never learned his name, and Granny never sold him anything. Still, I dreamed about him sometimes: I was always watching his blue Lexus driving away, sagging under the weight of whatever was crammed into it. Sometimes just chests and chairs, but once it was Granny and Ed, both rolled up in packing tape and staring back at me sadly.

Over the years it never mattered that the living room and dining room had emptied out little by little after those visits, or that overnight trips, restaurant dinners, and even movies were treats we had to plan for very carefully. No matter how bad things got, we always knew we had our insurance plan. Sell the Tapestry.

Granny always said Tapestry with a capital letter, like President. It was far and away the most beautiful thing we owned, a giant rug of gold, red, green, and mostly blue, filled with forest animals, birds, unicorns, and all manner of things that gazed down at us from a whole wall of the living room. Over the years, as one thing after another got wrapped up and carefully placed inside Mr. Nazhar’s briefcase, the Tapestry started feeling bigger and bigger, like a wall map. Or, when I was feeling especially lonely, a window into another world.

The Tapestry was woven by William Morris just before he died, more than a century ago. He’s Granny’s favorite artist, and she’s not the only one who feels that way. He’s not quite teach-him-in-middle-school famous. Still, a genuine work this size, designed by him and made in his own Merton Abbey Factory by the workers that he and his daughter had trained, had to be worth way more than the little painted tiles and scraps of manuscript Mr. Nazhar had been taking lately.

So when the bank threatened to take away our house a few months ago, I barely flinched.

“The museum will help you, Granny,” I announced cheerfully. “Just like before.”

Mr. Nazhar loves Granny; he told her he’d trade twenty interns in black stockings for a chance to put her to work at the museum. He’s always coming by to quiz her about her old days in “the Merrrton shop”: I love how he always says it just exactly like that, with a kind of purr in Merton, and shop like chop. “And did Morris’s daughter May supervise the textiles at Merrrton while you worked there, Georrrrrgie?”

Granny’s real name is Georgiana, which always makes me think of some Edward Gorey character in a long white gown, eating asparagus with a pearl-handled fork. She likes people to call her Georgie, or even George, but I think Georgiana suits her. Mr. Nazhar likes to eat Granny’s almond macaroons and ask her long-winded questions about textiles, and woodblock printing, and a load of things that most kids only come across on a field trip to Plymouth, or a family vacation at Colonial Williamsburg.

One day, when Granny was showing him how to embroider a valence using freshly dyed indigo thread, Ed leaned over and whispered, “Jen, don’t tell him that nobody cares about the stuff Granny knows anymore.” I whispered back, “Nobody but us!” He looked down at the copper plate where I was doing my best to engrave something recognizable, using Mom’s old burins and burnishers, and he gave a little nod.

The money from the museum was our lifeline. After our parents died, all of Granny’s old students had stopped coming. Partly because weaving and printmaking get harder to teach with arthritis, but also because we started to scare people a bit. I think I even scared Eva sometimes, and she’s supposedly my best friend. Back then, Granny was easy to classify: a lovable old immigrant (what an adorable accent!) with her artist daughter and a son-in-law who taught shop at the high school. It probably helped that my dad also built hardwood furniture that ended up in a lot of our neighbors’ living r

ooms.

Things kind of changed after the accident—I mean, when it was just the three of us. Ed was only five then (I was eight) and he was liable to start yelling, really yelling for Granny’s help when he couldn’t get one of his notebooks exactly the way he wanted it.

Eva once told me everyone was expecting “some nice family” take us in. Granny worked hard all her life, but what she worked at never had much to do with packing lunches and showing up for school plays. Mom had been her only child, and that was forty years ago.

Still, she stuck it out, and so did we, learning her rules little by little. Whether it’s fixing the lawn mower, cooking, or making new clothes, Granny will always do it first. But I better be watching so I can do it next time. And teach it to Ed the time after that: See one, do one, teach one.

On top of that, Granny somehow still manages to come up with new basketball shoes for me every season, and an endless supply of drawing paper for Ed. Even though we can’t buy all the poetry books I’d like—in fact, we can’t buy any—my dad left a pretty good collection, and the library is only four stops away on the subway. On a good day, maybe practicing archery in the backyard with the arrows Granny taught us to fletch, Ed will shout “Jen, Granny! We’re the unholy Trinity!” and for just a minute, everything seems perfect. Almost.

Granny, meanwhile, was still reading Mr. Nazhar’s letter. He really did want things to work out—said he was working on a plan that would be even better than just buying it from us, a plan that would keep us in our house and Granny connected to the museum. But the trustees of the museum, the ones with the checkbooks that really mattered, couldn’t accept that the Tapestry was designed and made by William Morris and his Merton workers.

Their problem was simple: The Tapestry wasn’t finished. It had about a dozen places where the weaving just stopped, and all you could see was the bare cream-colored warp. It was like looking at a TV that was perfect in most places, but dissolved into dead pixels right where you most wanted to see.

I didn’t need Mr. Nazhar to tell me about gaps in the Tapestry. Even though they’d never made me doubt the Tapestry was actually by Morris, the Lost Spots (I use capital letters for them, too) haunted me. When I should have been paying attention in geography class, my brain would keep telling stories about them. About a gap in a meadow, or a clearing in the forest that looked as if some giant snaky animal had been peeled right off the picture.

Take the lower left-hand corner, where a redheaded girl in an emerald gown was stretching her arm way up beneath a blossoming tree. Her fingers were just about to close around a little empty circle that I could swear was meant to be an apple. Her expression had always puzzled me. It was so sad, as if she knew that her fingers were closing not on an apple, but on empty space. I was convinced that if the apple had been there, her expression would have changed.

Ed was more practical. He made a diagram that totaled up the number of missing square inches. “Granny,” he started firmly, “I don’t think there are more than a dozen gaps in this tapestry. There’s this open space up here in the sky and what looks basically like a river down here, and a really fat pony, and this could be two squid quarreling over a ball of yarn, and …” He trailed off again, looking up at me for guidance, thinking maybe I’d tell Granny about the Lost Spots.

I couldn’t do it. I slumped back on the sofa and peered over Granny’s shoulder, not bothering to take off my clumsy gear bag, ignoring the way my basketball shoved into my spine. No way would the drawings I’d had Ed make, or the elaborate stories I’d tried out in front of the Tapestry, be the kind of proof Mr. Nazhar could bring to the trustees. Even he would only have smiled and looked down into his tea. His idea of evidence didn’t have much to do with the stories I told. I pictured his earnest face, his mustache lightly sprinkled with almond macaroons, thinking about how it lit up when Granny produced an actual shuttle from “the Merrrton shop” or a “verrified” piece of William Morris stained glass. Why would he believe my story about a missing dragon under the oaks, or my idea of what it felt like for that girl to reach up and have her fingers close on nothing?

I could tell the letter had gotten to Granny also. All those years back in England working for the company that Morris himself had founded, all those years spent learning how to weave, to embroider, to paint tiles, and all the rest. Wasn’t she, herself, all the proof Mr. Nazhar could want? Look at these hands, she might have said to Mr. Nazhar. Don’t you think these hands would know a Tapestry by William Morris?

I wish,” Granny began, unusually fierce, “I simply wish …” Ed and I shot worried glances at each other. I remembered, just once, looking inside Granny’s dresser and finding a note from Aunt Cathy, Daddy’s horsey sister, warning Granny how “unusual and reckless” it was for someone in her eighties to take a pair of “rambunctious children” into her house. “There are state-sponsored alternatives …,” the letter went on; I’d dropped it and run out of the room.

Looking at Granny now, seeing how her hand shook over the letter, I was really glad I’d never mentioned that note to Ed. “I wish,” Granny said a third time, and then her face cleared and she laughed, “I wish that we could ask advice from the only truly sensible member of this family!” And she shot her usual fond look over at Mead.

Granny is very fond of fond looks, and especially fond of Mead. So am I. He’s the only tame blackbird I’ve ever even heard of. When he’s not trying to hide pebbles in my hair or peck holes in my basketball, he might be my favorite member of the family. It struck me that his cage was about the only other beautiful old thing that hadn’t made its way to the museum—yet.

As usual, Mead tilted his head sideways at her and whistled softly. Then he flicked his wings a bit, and gazed up and away—remembering something, maybe. I couldn’t help asking, for the millionth time, “But Granny, how do you know? You always say it was by him, but really, really, how do you know?”

Usually when I say that, she just shakes her head in that I’m so learned, I can’t help it way. Today, though, she leaned back and polished her glasses.

“I don’t think I’ve ever mentioned this before, Jen—” There was one of Granny’s dramatic pauses, and I could hear Ed frantically flipping over pages in his notebook in case Granny said something he could add to his tidy list of Tapestry Information. “I know the Tapestry was woven by Morris,” she went on finally, “because she told me he’d made it when she gave it to me. Along with a little poem.”

As she spoke, it was like a match scratched against something in my brain and started to sputter. Ed inherited my mother’s drawing ability, along with her beautiful artist’s pencils. I got something else instead: these memories, so vivid but so hard to place. So, whenever I see a chubby man walking next to a slightly taller redheaded woman I get a little lump in my throat. That’s obviously something about Mom and Dad, right; but what? Am I seeing some special moment, or is that image the condensed summary, like a little memory stick that I somehow loaded up with their whole lives?

This was a throat-lump memory, too, but a new one. I was in a lap, it was evening, I could see Dad in front of me with a little green book, gold lettering on the spine. I knew somehow it was an old, old poem about a girl who’d lost something. When I closed my eyes, I could even hear the rhymes.

“Queen,” I whispered, and then right away: “unseen.” I struggled, waiting for more to come. The lap was warm; and I was pretty sure that right next to me was a little baby sleeping (could that be Ed?).

While all those thoughts about my parents (and all my resolutions not to think about them) were running through my head, Granny smiled at me and opened her mouth to speak. Before she could, though, I suddenly said “fell and well.” It felt so good, I said it again: “Fell and well!” Like picking a scab, it ached, but it felt so good. Only what did it mean?

CHAPTER TWO

What’s Undone

All this time Ed had been jabbering away frantically like a radio nobody remembered to turn down. I tu

ned him back in. “Jen? Granny? Can someone please tell me what’s going on?”

“It’s nothing,” I said quickly. “When Granny mentioned poetry I suddenly thought about Dad reading something to me. No idea why.”

“Maybe because Dad always used to mutter poetry to himself when he was working.”

“What? That’s impossible, Ed!” I said hotly. But was it? After all, how could I remember what I’d forgotten? There were so few memories, so many empty spaces. At least the Lost Spots in the Tapestry had a shape, a blank to be filled in.

Granny pulled her chair past Mead’s cage so that all of us faced the Tapestry. Folding Mr. Nazhar’s letter and tucking it with steady hands back into its envelope, she locked her eyes on the Tapestry. “There are some memories that have been with me so long, I can hardly see them anymore. They’re a part of my apprenticeship—my childhood on the wane, my youth as it gave way to age.” Granny has these phrases that pour out of her and I’ve learned that rather than asking her to define every word, sometimes you just have to let it flow over you like a waterfall.

“What I remember about the Great Depression, in our poor little corner of London,” Granny began (“Pimlico,” Ed muttered, fingering the neat row of pens in his shirt pocket, “you lived in Pimlico”), “was that parents couldn’t work, and children had to. I minded less than most of my friends, though, working at the Merton Abbey Factory.

“A shadow of its former self it was,” Granny continued, “melting ever so slowly away since William Morris himself had died back in the 1890s. To me it was a job still, a paying job and glad to have it, thank you kindly! One day, though, when I’d just turned fifteen and gotten my first rise in pay, she came to sit by me at my loom. Though she was not, most definitely not the kind to cry at work, her eyes did seem red.”

Time and the Tapestry

Time and the Tapestry